Many bloggers and small businesses build websites using service providers such as WordPress or Wix, and friends and family find them using names like mysite.wixsite.com, or mysite.wordpress.com. This is okay for a hobby. But it doesn’t work for anyone trying to build a real identity. Spend a few minutes to set up your own Internet identity and look like a pro. You can still use Wix, WordPress, or your favorite service, but now the outside world will find you by your name instead of the service you use.

This graph from the United States Census Bureau summarizes why setting up your own Internet identity is a good idea. From Q1, 2008 through third quarter, 2017, US e-commerce sales steadily grew from 3.5 percent of all retail to more than 9 percent. In non-quantitative language, this means sales over the Internet are growing faster than brick and mortar sales, and the trend shows no signs of slowing. This is especially important for authors like me because Amazon is crushing every other sales channel in the book market. The world is moving to doing most of its business over the Internet, and my books need to be there.

The challenge, of course, is phrases like “domain name” create FUD (Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt) in people’s minds, and many think setting up an Internet identity is prohibitively expensive. If you’re one of these folks, don’t let FUD win. It’s not expensive and it’s not rocket-science.

Note that I said “Internet identity” and not “website.” The difference is crucial. Your website is a critical component of your Internet identity, but it’s not the only component. My Internet identity has several pieces besides my website under my dgregscott.com domain name.

It all starts with DNS, for Domain Naming System. DNS is a mixture of politics, business, and technology. Everyone who uses the Internet should know what DNS does and how to navigate it.

DNS

The concept behind DNS is simple: translate names to IP Addresses. Think of an IP Address as similar to a telephone number, but on the Internet. DNS resolvers, also called DNS servers, manage all this. If I want to access the website at, say, www.dgregscott.com, I first query the DNS resolver assigned to me to retrieve that website’s IP Address, and then send my web request to that website’s IP Address. The metaphor of looking up a telephone number in an old-fashioned phone-book and then dialing the phone helps visualize the process.

DNS names follow a well-defined set of rules. They start with a top level domain name, or TLD. The Internet used seven TLDs in its inception – .com, .org, .net, .gov, edu, .mil, and .int. Today, ICANN, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, assigns TLDs. Anyone with around $200,000 to spend can file an application and request a TLD, and today’s Internet supports about 1500 TLDs. But .com will continue to dwarf them all because everyone wants a name in the .com namespace.

ICANN also assigns a two-character TLD to every country in the world. The United States TLD is .us. ICANN assigned .tv to the South-Pacific island country of Tuvalu, and Tuvalu supports a significant portion of its economy by leasing .tv domain names to media companies. It’s a great story about mixing technology, business, and politics.

Underneath TLDs are second-level domain names. These are the familiar names such as google.com, whitehouse.gov, redcross.org, and, millions of others, including my own, dgregscott.com. And underneath second-level domain names are additional subdomains and hosts. Second-level domain registrants can assign names and subdomains in their namespace as they see fit.

The fully qualified domain name (FQDN) for my website, www.dgregscott.com, consists of the hostname, www, followed by a period (.), and my domain name, dgregscott.com. I also have a few other hosts for different services I offer, including ftp, mail, and others. Like most domain names, dgregscott.com has no subdomains, and I don’t see a good reason to use them. The United States .us namespace uses subdomains, as do some other countries. The website, www.state.mn.us, for example, points to the official State of Minnesota website. But that name redirects to an easier-to-digest name, mn.gov. Simple and easy to remember is good.

By convention, we use the hostname, www, for websites, mail for email servers, ftp for ftp servers, and a few others. But nothing enforces this convention. We also have a concept called a default name, which points the domain name without a hostname to a specific system. Since websites are the most popular application on the Internet, most default names point to the website associated with that domain. Browse to dgregscott.com and end up at the same website as https://www.dgregscott.com.

And that leads to name registration. How does somebody acquire a domain name?

Name Registration

Full disclosure here. I am an Internet domain name name registrar. I resell a service from Network Solutions, the original Internet domain name registrar, and I manage the records for a few domain names, most of them my own. As of this writing in Feb. 2018, I have no desire to ramp up this business. I do it on a small scale for my own convenience and for a few others. Typical cost is $20 per year per domain name in the .com namespace.

Many website operators bundle domain registration with website hosting service, and many people and organizations use it because it’s convenient and they don’t want to understand how it works. This is a mistake. Your domain name is your Internet identity and it may be even more valuable than your trademark. Nobody else should have the power to hold it hostage. Take a few minutes and learn how to register and manage it yourself for your own safety.

Here’s how to do it.

The first, and most important step is finding a name not registered to anyone else. Do that by performing whois lookups on name possibilities. Whois is an Internet service that returns information for registered domain names, and one easy way to perform whois lookups is with the whois website, at http://www.whois.com. If you find a name not registered to anyone else, you’re free to register it.

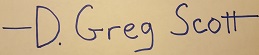

An obvious possibility for my domain name was gregscott.com. But an artist in Georgia named Gregory J. Scott registered gregscott.com years ago, and he uses his website to sell paintings. How do I know this? Here’s a screenshot from a whois lookup.

Gregory J. Scott has as much right to the gregscott.com domain name as me, and he registered it first. I doubt he is willing to give it up. So I chose to build my Internet identity around the name, dgregscott.com. D for Daniel, my official first name.

Once you find a name you like, set up a free account with any domain name registrar, fill out a form, charge between $20 and $35 to your credit card for a one year lease (some offer discounts for multiple years), and you have your own domain name. It really is that simple. Network Solutions, Godaddy, and Tucows are popular domain name registrars. There are dozens of others. I like Network Solutions and its sister Web.com companies because they’ve given me good customer service over the years. I’ve also dealt with Godaddy. Use Google or your favorite search engine to find one you like. Or twist my arm and I’ll do it for you.

Sometimes, people register names they hope will become popular. This is where technology and extortion meet, and it’s the Internet equivalent of buying up blocks of concert tickets and scalping them. One example – somebody registered the name, startupinvestors.com, and is now auctioning it off. As of this writing, apparently, the highest bid so far is $1040. Or, maybe the seller is lying and trying to pump up the price. I hope he chokes on it. Here’s an amusing article from Wired Magazine back in 1994 about mcdonalds.com during the original Internet gold rush.

What if somebody else already controls your perfect domain name and it’s the only name that works? Here is a blog post with some thoughts on how to proceed. And here is an article about one person who might control the name you want.

When you find a name you like, also look for similar names and grab them too. The website, www.paint-can.com apparently belongs to an artist in Toronto. But the domains, paintcan.com, paintcans.com, and paint-cans.com all appear to belong to extortionists. And paint-cam.com (m and not n) is up for sale. Connecting with customers will be more complicated than it should be for this artist because so many similar names point elsewhere.

If you’re a nonprofit and you register a .org name, protect yourself by also registering the equivalent .com name. If the name you want is taken in the .com namespace, don’t try to use the equivalent name in the .net or other namespace. It looks amateurish. Dot net names are for companies that do something around managing the Internet, and other organizations who register .net names only create confusion.

After registering your domain name, make sure you keep up your renewal. If your name registration expires, it’s a good bet an extortionist with automation that watches for expired names will scoop it up and offer it back for lots more than you spent to lease it the first time. You might be able to fight it in court, and you might even win after several years and a boatload of legal fees. Don’t put yourself in this position.

And that’s it. Now, you have your own Internet identity and you can put it to work by building a website, setting up an email address, and setting up other services you want to offer.

Putting your Internet identity to work

You’ll want to point a DNS host (A) record under your domain name to your website IP Address.

Query your web hosting provider to find out the website name and IP Address assigned to your website. The name will most likely be www. The web hosting provider may offer to handle DNS for you. Don’t do it. This gives your web hosting provider too much power over your overall Internet identity. Instead, keep DNS with your domain name registrar, and set up your host (A) record yourself. Any web hosting provider should be able to easily accommodate that.

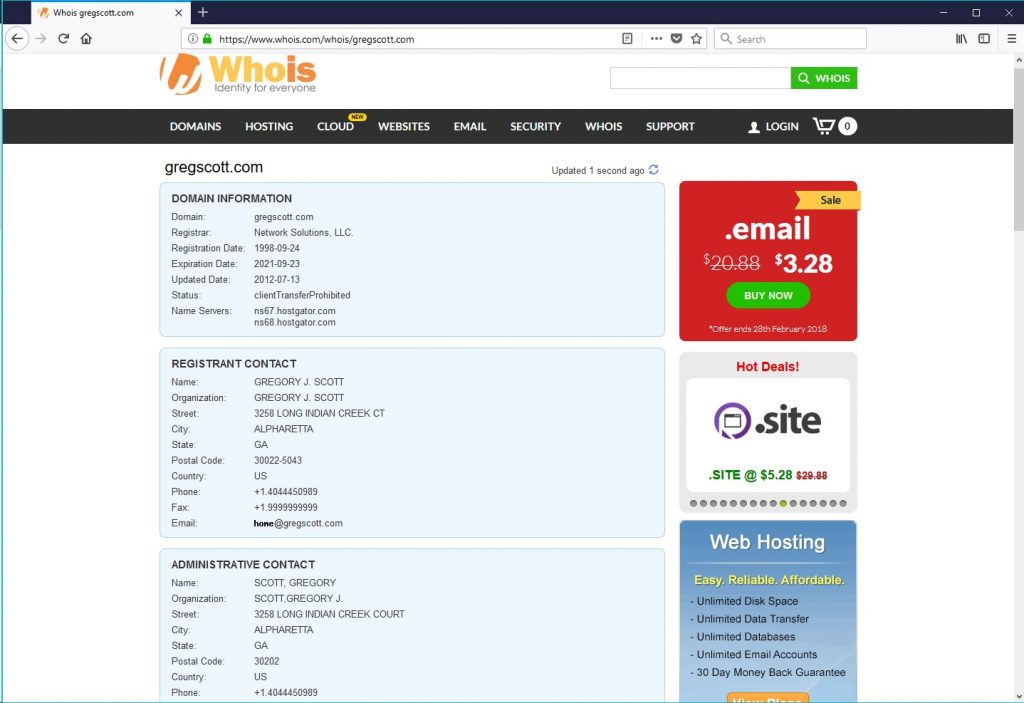

Here are the host (A) records I set up with my domain name registrar for my dgregscott.com domain:

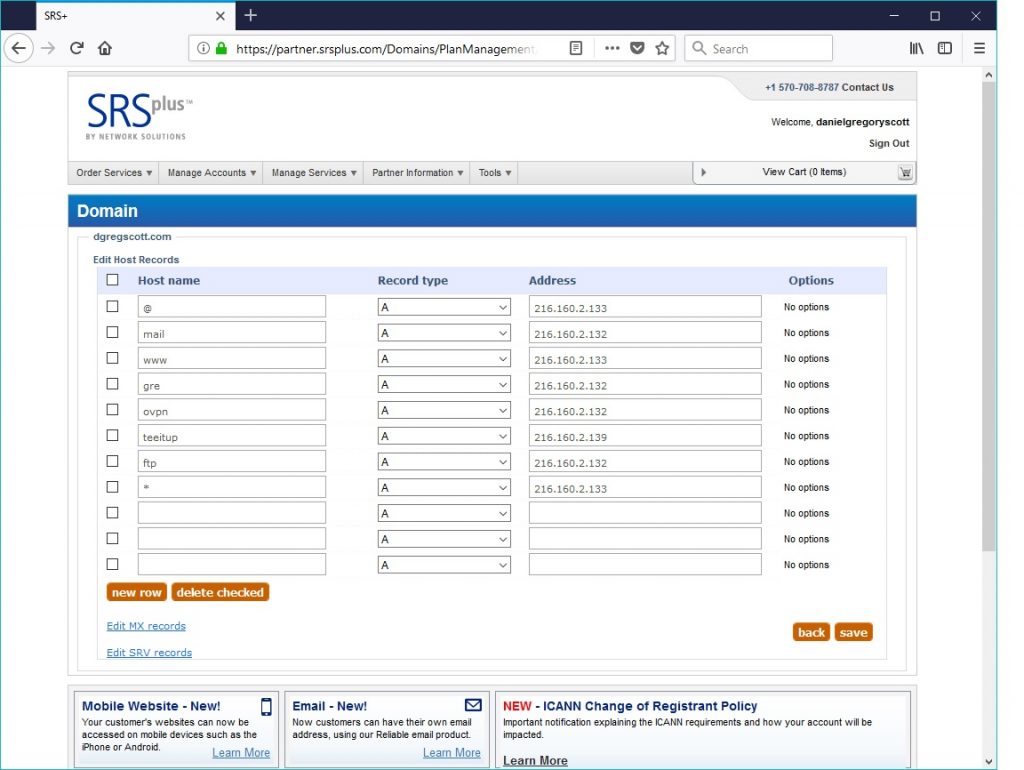

You may also want to set up a Mail Exchange (MX) record for email. This is a special record describing the name of the server that handles email service for your domain. I host my own, and I set up a host (A) record cleverly named, “mail” with its IP Address. Next, I need an MX (Mail Exchange) record to point to it. Here is what mine looks like:

Your email will most likely be with a commercial service provider, such as Google, Microsoft, or your web hosting service. They will have their own host (A) records associating the name of their email server(s) with the appropriate IP Addresses, and so all you’ll need in your own DNS is an MX (Mail Exchange) record to associate email for your domain with the name(s) of their email server(s). You’ll also need to work with your email provider to make sure their email servers accept inbound email for your domain.

Once you set up your MX record, email to yourname@yourdomain.com should flow right into your inbox. Combine that with your website at www.yourdomain.com, and your identity to the outside world will be on an equal footing with the largest corporations on the planet. And, if you become unhappy with an email or web service provider, you can move either one by changing your DNS records.

Don’t be intimidated. If you learned how to drive an automobile in traffic, you can learn what you need to set up your own Internet identity. Invest a few minutes to understand how this infrastructure works, establish your Internet identity, and become a full-time member of the digital economy.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks